Independent music harmony

Activities for introducing independent harmony to children.

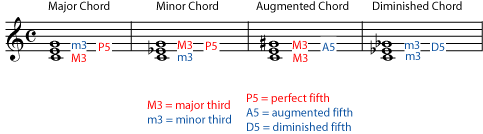

A harmony is independent of the melody if it is often doing something different from the melody. Even if it is not independent enough to be counterpoint, such harmony adds more depth and interest to the music than drones, parallel harmonies, or simple chordal accompaniments. So this type of harmony is extremely popular for hymns and other choral arrangements, and it is also very common in instrumental music and in instrumental accompaniments.

What makes a harmony or accompaniment part independent?

If it often has different rhythms than the melody, it is independent.

Even if it has the same rhythms as the melody, it is independent if it is often moving in a different direction from the melody; for example, the harmony part is going down when the melody is going up.

If a harmony is truly independent, then even when it is moving in the same direction as the melody, it is usually moving by a different interval. For example, if the melody is going up by perfect fourth, it might go up by a single half step.

Independent harmonies are not quite counterpoint. In order to be considered true counterpoint or polyphony, the different parts must be not only independent, they must also sound like equally important melodies. Is there always a very clear line between independent harmony and counterpoint? No! Remember that all of the rules and definitions in music theory (“counterpoint”, “harmony”, “minor keys”) were all made up to describe what good composers were already doing; they do not define what a composer is allowed to do. If the composer – or performer – likes, an independent line can easily drift back and forth between being a background, harmony part, and being so important that it becomes a countermelody.

Music Accompaniments

But in much classical and popular music, there is one line that is clearly the melody. The harmonies or accompaniment parts are all clearly “background”, but they still follow most of the important rules of counterpoint. The most important rule of counterpoint is that two lines should not move in parallel. In other words, when the melody goes down one step, the harmony should do something other than going down one step; it can go down by a different interval, or stay the same, but it is best if it goes up. When the melody goes up a perfect fourth, the harmony should do anything other than go up a perfect fourth. Independent harmonies also follow this rule.

For much homophonic music, following this basic rule about contrasting intervals is enough. In particular, there is a great deal of choral music (most traditional Western hymns, for example) in which all the parts have different intervals but use the same rhythms, so that everybody is singing the same word at the same time. This type of texture is sometimes called homorhythmic.

Other harmony or accompaniment parts are even more independent, and have a different rhythm from the melody also. Good examples of this are the bass line in most pop songs or the instrumental parts accompanying an opera aria. In these types of music, as well as in much jazz and symphonic music, there is one line that is clearly the melody, but the other parts aren’t simply following along with the melody. They are “doing their own thing”.

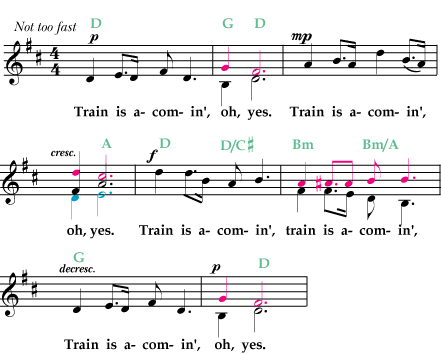

Train is a-Comin’

The notes in black are the melody. Red notes are an extensive high harmony; give this to a few students who are ready for a challenge. Blue notes are a very small low harmony part, which can be ignored if you like; if you have a few more students who can sing a few notes that are not in the melody, give this part to them. Everyone should sing the melody whenever they do not have a harmony part.

Suggested listening list

Almost any chorus from a Gilbert and Sullivan opera.

Recordings of choirs singing traditional (nineteenth-century) hymns.

If you have trouble hearing hymn harmonies, try listening to the chorales of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (Weinachts Oratorium). The chorales are not contrapuntal – the melody is clearly in the soprano part, and the different parts sing the same words at the same time – but it is unusually easy to hear that the parts are in fact quite different from each other.

Pop music with a solo singer, a strong bass line, and interesting instrumental accompaniment.

Most opera arias and many opera choruses.

This is also one of the most common textures in orchestral music, particularly in classical-era and Romantic-era symphonies (Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, etc.) But be aware that in symphonic music, texture can change often and quickly.